One of the most profound effects of the monochrome palette is to make us notice what is not there. When we see a monochrome world, there is an implicit suggestion that something is missing, not only visually but also thematically. We tend to see the monochrome game world as a stylistic shorthand for sadness, loss, melancholy, and other subjects that can ruin a Sunday.

Rusty Lake's "The White Door" certainly does, but in this combined point-and-click and ayahuasca journey, it raises the question of what is missing, not only figuratively but literally. The small changes in routine imposed by the white coat behind the white door, the empty white plate instead of the meal you are accustomed to receiving at exactly 5 p.m., these feel like significant narrative revelations within the minimalist confines of the cell.

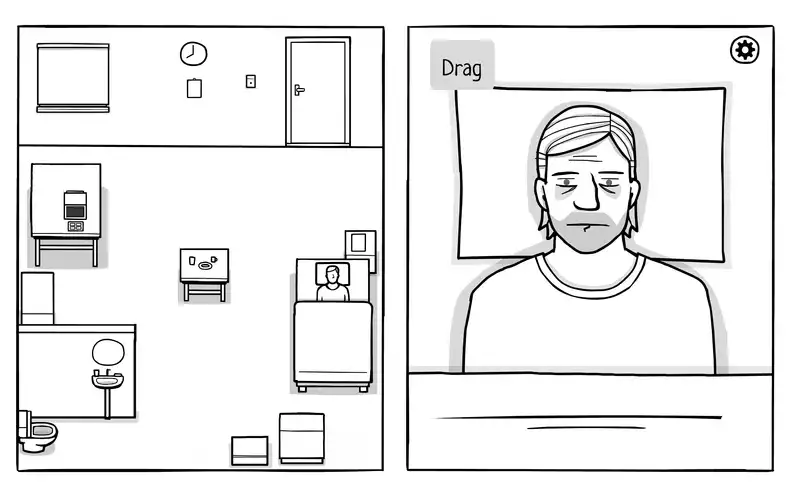

You are Robert Hill and the year is 1972. Because that's what it says on your wall calendar and on your driver's license in your drawer. Otherwise, where and why in your life, most importantly, is why you ended up in a mental health facility. What follows is a few days of hourly mundane routines prepared for you by strangers who hope they care about you. [The mundane tasks, such as brushing your teeth at the same time every morning, push the player further and further into a corner.

This trick works especially well in games because we are trained to suspend our disbelief, to forget that we are following the game designer's script and just immerse ourselves in the task at hand. Nevertheless, the fact that it is employed so well elsewhere weakens its impact here. I was taken aback when lines of code began infecting the once-cheerful arcade games in "Pony Island," when children's images were defaced with satanic symbols, and when the dingy examination rooms in "Portal 2" began showing faint signs of life outside their walls. Years later, in "The White Door," rats and shadowy figures invade a sterile room.

While you poke at the bits and pieces in between games, Robert also escapes into dreams, going somewhere else in between monotonous days. Here, a story begins to form about how he ended up behind the door that bears his name, and why he looks so gloomy in the mirror every day.

Mechanically, it's always a light touch. A coffee cup is drawn to Robert's lips as he talks about taking another sip of coffee in a dream sequence, or he answers a choice question in a daily psychological test. As the progression progresses, it becomes more like a traditional puzzle game, employing pattern recognition and logical challenges at the gate, but the stark, reality-bending tone of the "white door" means that the rules are never clear.

Sometimes that's a good thing. Because you can just go with the flow of the journey without wondering why doing X will yield Y result. Just as the magical realism of "Kentucky Route Zero" led to tuning out the radio without knowing why, sometimes playing with the images presented and challenging our assumptions about them is the key to moving forward.

Note that I said "sometimes." Point-and-click runs the risk of obfuscating the logic of the puzzle ever since Ron Gilbert was identified buying beer. It is certainly not logical, and some puzzles are too abstract to be satisfying when solved. In any case, there are links to developer tutorials for each level and an option within the game options to ask the game's Discord server for hints, so you really can't get stuck. All puzzle games: this one please.

Games dealing with mental health issues are becoming increasingly common, but this game is less subtle than its ilk. Darkness and color. Muddled memories. The Ominous Psychiatric Ward: ...... All the classics are here, and its opaque narrative is also conventional. The ambiguity of the story may be aimed at literary complexity, but, well, it just seems to take the easy way out. It mixes things up with dreams and illusions, leaves some questions unanswered, and expects the player to solve the rest.

Despite this, I found the subject matter much more difficult than the puzzle. Without delving into the details of the story, "The White Door" is a game that makes you feel the worst you can possibly feel, and the slight brushstrokes and voice acting make it uncomfortably effective at putting you in that kind of mental space. It is also a game of feeling better, of losing the color of life, of enduring the joyless passages, of getting out the other side, of finding beauty in the trivial and the simple. We can all find personal relevance and significance in it.

In two hours, using art assets that, while well drawn, would not look out of place on Newgrounds because of its minimalism and economy of resources, a white door gets under your skin and makes you feel what it is like to be someone else. It's not a series of explanations or puzzles, but rather an experience of Robert Hill's scheduled life, bathroom trips, etc. It is certainly effective in that it takes you to an unpleasant place and makes you feel the emotional truth that things will get better.

.

Comments